by Omar Pimienta

Every nation hates its children.

this is a requirement of statehood.

—Solmaz Sharif

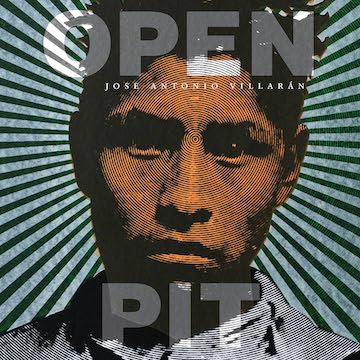

Reading open pit was a complex process for me. Before reading it, I had approached the orality of the text through various public readings of the manuscript, and these had triggered in me the need to understand how Villarán was going to resolve conceptually and formally, in a book, all those threads that emerged from the same theme: approaching extractivism in Peru from a distance and the vicissitudes of living as a graduate student in California. I have waited for the book for just under a decade, I have seen the manuscript grow, expand, contract, and now that I have it in my hands as a concrete, finished, published object, I must write a review. As you will understand, this review is not intended to be objective and much less academic. Jose Antonio Villarán has been my colleague during graduate school in San Diego and teammate at the soccer field in Tijuana, a poetic accomplice, but above all he has been a friend, and it is perhaps for this reason that I thought I understood where Villarán writes from and for whom open pit is written for. At first, I thought my reading of the book and this review could be more useful for readers if I visualized myself as an “insider,” but nothing could be further from the truth. When I closed the book, the opposite occurred; I had as many or more questions than when I opened it and I understood that Villarán had achieved something important: infecting me with his uncertainties: “I feel more knowledgeable on the subject / and at the same time / more confused and discouraged.” I can’t even say that I feel more knowledgeable about the subject, just confused and discouraged, with many questions. Villarán does not give you answers — he does not have them — but he invites you to question everything, and it is in this exercise where poetry is the best tool, answers do not matter as much as making the reader formulate their own questions, the labor of uncertainty as means to build yourself a reality.

The first question triggered by my reading was the following: in these increasingly globalized times, and beyond what’s inscribed into our genetic code, what is the most powerful concept that defines us as writers? Villarán’s open pit offers the following clue: class. Yet little by little, as I moved through its pages, I understood that nationality can have as much or more relevance. It seems that we can recognize more and more clearly the concepts that make us vulnerable; race, gender, class, sexual orientation and nationality, the latter being the most difficult to recognize because it is difficult to clearly recognize the fiction of “national being-ness” until you see it from afar. open pit made me think about how to write poetry from “a national being” when three nationalities are inherited within that being, three possible passports. What happens when you have divided your life into two countries that you can call homeland. Not only that, what happens when one of these passports symbolizes an economic system responsible for the exploitation of the other, when one of your countries could be the poster child for the global south and the other for the global north. How do you write poetry from two languages about those two nations when both are part of your subjectivity, and at the same time so diametrically opposed? How do you write while always being “the other,” regardless of how you are perceived? As the white academic at 4,540 meters above sea level in Morococha or as the Latinx poet in the hallways of a University of California? Jose Antonio Villarán does not offer you any answers, but from his pages he does what all poetry should do: he digs.

The Royal Spanish Academy and the Cambridge dictionary have similar meanings for the verb to dig: “Scratch or repeatedly remove the surface of the earth, delving something into it.” open pit is a poetry book that works like a shovel. Villarán scratches, loosens, and rakes, trying to remove layers of earth, a key word to understand the nation, because without land there is no nation, and without people there is no town. In Spanish, unlike English, pueblo means territory as well as people; the town of Morococha is removed, dug up, raked. In Spanish it is understood that it is the people, in English, not necessarily. This is another question triggered by the book: is this linguistic divergence, this difference between Spanish and English, the reason or the outcome of practices of settler colonialism?

Villarán writes:

there’s a town on the mountain

a bull with no horns

in order to reach the deposits

the people must go

as must the mountain

My translation:

hay un pueblo en las montañas

un toro mocho

para llegar a los depósitos

tiene que desaparecer

asimismo la montaña.

My translation does not have the word people because it would sound redundant in Spanish. It is often said el pueblo peruano, or el pueblo mexicano, and we all understand it is the people and not the towns that we are referring to. It is an insignificant difference, perhaps, but I would like to know if when someone reads in English that in order to obtain capital a town has to disappear, is it as shocking as when someone reads in Spanish that in order to obtain capital the people have to disappear? This type of inquiry, this work of digging into language can only be achieved from a space of linguistic privilege such as that of Villarán, a privilege given to him thanks to his dual citizenship and educational obstinacy, a privilege that in return marginalizes him as a poet who will never belong to a national poetics.

Since when, how, and why is a book like open pit written? Villarán starts writing from the moment he is trying to understand the forces that create his subjectivity as heir to multiple realities, that of being a Peruvian-American writer with a Mexican mother who becomes a father during this writing process and tries to navigate an academia that is increasingly becoming the very model of the system it pretends to criticize. How to write this book was the key that confused me the most and at the same time opened more poetic veins in my brain. With a schizophrenic poetic practice, in which he pretends to be the writer-parent, the people, capital, the extra-human and the government. Why write a book like open pit? Because it is necessary to understand your heritage; American poetics / Latin American poetics; the atavisms and freedoms that both languages give you; the sociopolitical baggage and colonial traditions implicit in your passports. But above all to try to understand all that Villarán is leaving behind: well-articulated questions to Miqel, to other writers, to the students of the future, clues for how to understand ourselves in an increasingly interconnected and sick world.

Omar Pimienta is a writer/artist/scholar who lives and works across the Californias. His artistic practice examines questions of identity, transnationality, emergency poetics, sociopolitical landscape and memory. He is an Assistant Professor of Border and Migration Studies in the Americas at UC Santa Barbara. He has published four books of poetry in U.S, México and Spain. He has won the Emilio Prado 10th International Publication prize from the Centro Cultural Generación del 27 Malaga Spain. In 2017-18 he was awarded an Art Matters Grant. From 2019-22 he was a Member of the Mexican Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte in the area of Poetry.