by Sam Moore

I

We’re holding hands at Golden Gate Park. Their jacket is thicker than mine, and they’re wearing my gloves; a Californian through and through, this clear, brisk day at the dawn of winter is too cold for them. I feel them squeezing my hand, lightly tugging me a step or so back, before I turn around and see the AIDS Memorial Grove. There’s an inscription, a quote from Bill Clinton: We must continue to work together as a nation to further our progress against this deadly epidemic. And while we do so we must remember that every person who is living with HIV or AIDS is someone’s son or daughter, brother or sister, parent or grandparent. They deserve our respect, and they need our love.

We’re spending the weekend in San Francisco before I fly through the night back to London. Our to-do list grows more expansive as we get closer to the drive that takes us to the outskirts of the city; to the cheapest hotel we could find, and a five-ten minute walk to a train station that will take us into the city itself. We’ve only got a full 24 hours in San Francisco. There are plans for museums, galleries, bookstores, restaurants. We stumble on the memorial accidentally. It feels like serendipity. I want to reach out and touch it, leaving my own fingerprints on this piece of history, but I stop, hold myself back. I imagine that touching it would imprint me, my presence, my history, within this lineage. If this is enough of a lineage; what we’re able to do with only the fragments we have left, and these towering, immovable monuments to what we’ve lost.

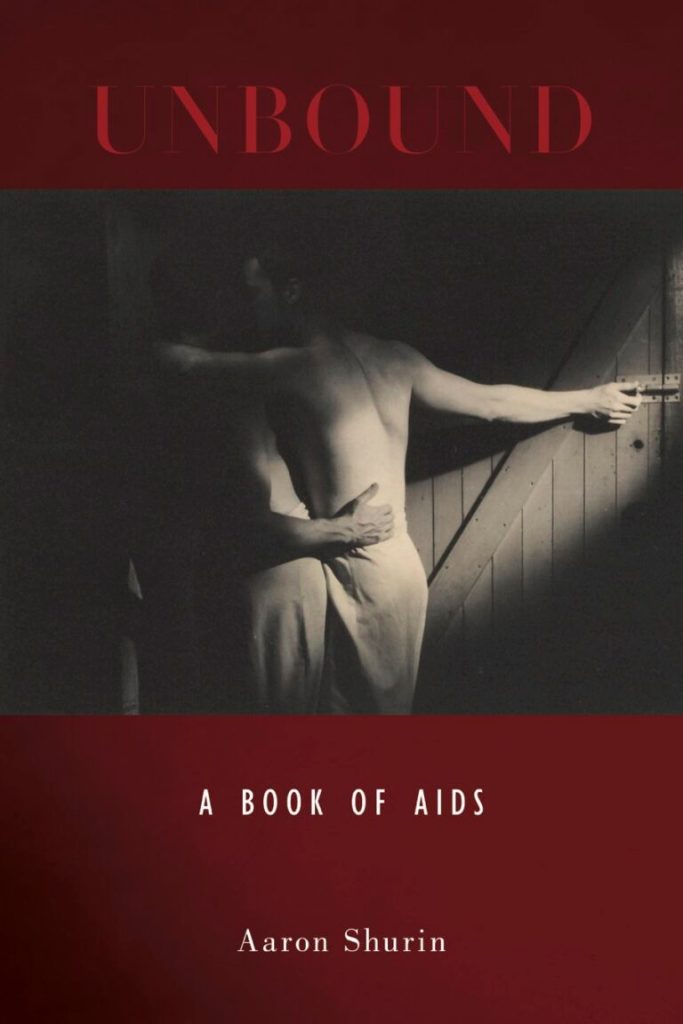

Aaron Shurin’s Unbound: A Book of AIDS is an exploration of this tension—the push and pull that exists between lineage and loss. Even the title captures this precarious feeling; the idea of a book—this book—coming undone, even as the reader holds it. A literary legacy is the one that people think of the most—the one that I keep returning to—something that’s bound. Permanent but precarious, in something as light, delicate, fragile, as paper.

Shurin evokes his friends, reading these drops on paper, and I wonder if they’re drops of ink or drops of blood. When I wrote All my teachers died of AIDS, a personal, cultural, half-remembered meditation on living a generation after the AIDS crisis, I described the virus, its impact, and the inaction surrounding it, as seeping into the bloodstream of history. Ink and blood have been bound together in my head ever since. Potent drops that seep through so much more than pages. Shurin describes a gland on a friend’s neck bursting open, hemorrhaging, becoming the mouth of hell. This dying friend asks their lover to be taken outside, so he could bleed into the earth. Shurin calls this communion. It makes me think of the Memorial Grove at Golden Gate Park; the blood at the roots of a monument like that, in the soil, the depths of it.

The Memorial Grove looks impeccable. I have a picture of it on my phone; blurry and imperfect because the phone case is too big for the phone itself, and cuts off the top corner of the image. There’s an irony to how pristine it looks, for the history that it speaks for. I remember decades ago, in history classes, we were shown ways that we could make things look old, like artifacts for a project. The example was always a map. We were told to use cold, damp teabags to weather the paper, to age it. There was this idea that for something to look like a genuine historical artifact, it needed to look old; the antithesis of how I understand this history now: something that never got to grow old.

Unbound has an interesting relationship to this history. This latest edition, published by Nightboat Books, features a new introduction, with the older ones now forming an epilogue. This change, to what comes pre- and post- in Unbound, creates a complicated relationship with history. As if Unbound is talking to itself, because there’s nobody else there to talk to. In the new preface, Shurin describes Unbound as a book that’s been revived. This act of revival is another way in which Unbound makes contact with the shadow of death. And in many ways, this shadow, the death that defined so much of the AIDS crisis, is the only history that we have left.

Amidst the formal transformations of Unbound is the transcription of a performance piece: Turn Around: a solo dance with voice. Shurin dedicates this performance to John B. Davis. Davis was born in 1964, and died of AIDS in 1992. As I write this, I am 28-years-old, the same age that Davis was when he passed away. Turn Around was first performed by Ney Fonesca in 1992. The transcription features an OFF-STAGE VOICE, and a dancer. Here, the dancer’s lines are attributed to NEY. The voice that pushes forward the story—the memory—of Turn Around is telling John’s story. Ney protests that the voice only ever tells them the same story, a story where John looked down at himself lying there. It offers to tell him a different story. A variation on a theme, with the opening line: Ney Fonesca looked down at himself lying there. Ney protests this is unfair, rages against it. Only to be told that this is a story about becoming a story. It has to be told. It has to be put into the past. But I don’t think that Unbound is about taking these stories and putting them into the past. Instead, through these constant reissues, reiterations, returns, Unbound is about bringing the past into the present; making it impossible to ignore, and giving people the space to reckon with a legacy of loss, and why sometimes, there’s no need for anything new to come and fill up that space.

II

One of the most challenging—emotionally and intellectually—parts of Unbound comes from Shurin trying not just to create space for this loss, but to imagine himself within it, as if this is the one place where he might be able to feel kinship with the friends that have been lost. My Memorial was written in 1994, the year that, according to a timeline of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the United States, AIDS became the leading cause of death for all Americans aged 25 to 44. It’s no wonder that My Memorial is exactly that, and that Shurin tries to lay it out with something approaching grandeur, or a gesture towards peace at what might feel inevitable. Shurin describes an elaborate stone chamber, the setting of a “fatal stone,” and a series of voices performing O Terra adio, a mournful piece from Aida, which translates to O Earth, farewell. What sounds at first like the description of a performance of Aida itself is quickly undone by Shurin, who instead confronts you directly with the idea of his loss, and the cause of it: I have died of AIDS, and this is my memorial. He describes the voices of the singers who will intone this aria—Aprile Millo and Placido Domingo—at his memorial as unbounding, which is to say, limitless. In a way, Shurin himself becomes limitless here, able to at once witness and enact his own memorial. My Memorial is thus pulled in two directions. As much as Shurin lingers on death—something as simple as a parenthetical (yet) in reference to dying cuts deep—it is the loss of others that moves him, and what this means for how he himself wants to be remembered. A self-professed opera queen, drama queen, he takes us through a series of records, operas, arias, a way of trying to keep his memory alive, flickering, even as that brief candle threatens to go out. He calls it the power of art to encode affection itself. I’ve often thought of art—both what was made, and what never had the chance to come to light—as being the legacy of the AIDS crisis, the ways in which we try to make sense of it. The ways in which we fail to. Shurin ends his hypothetical memorial with the words listen: remember me, and I wonder if that’s all we can do.

III

Whenever I write books, I put a lot of weight on the titles, epigraphs, chapters, and sections. They’re my first way into it, a kind of north star that I’m able to keep returning to, to see if I’m on the same path that I was at the beginning, and what it might mean if I’ve deviated. Right now, I’m trying to write a novel, and one of the first things I tried to do was find an epigraph, an anchor. I settled on a line from Rachel Cusk’s Transit, the second book in her Outline trilogy: “Maybe it’s only in our injuries, he said, that the future can take root.” For all of the formal codes I’m trying to crack, and structural decisions I need to make, I keep returning to this one sentence: this idea that the book is about healing.

It was easier to find the epigraph for my first book: I told myself that I was going to write about rage today, but instead, I’m writing about elegy Can one write both with rage and elegy? (Kate Zambreno). I’ve been thinking about it, and about the book, in my time with Unbound. I’ve found myself gravitating towards Shurin’s anger, to the voice that rages against unfairness in Turn Around, the desire to bleed into the earth. The latter reminds me of the ending of Buddies, the 1985 film by Arthur Bressan Jr, and the first to tackle the AIDS crisis. In the film’s final moments, David, a “buddy”—someone who volunteers to spend time in the hospital with a man dying of AIDS, giving them companionship at the end—is shown as the lone protestor on the lawn of the White House lawn, with the strings of the New York Salon Quintet aching in the background. This in itself reminds me of another moment; of The Jacket, worn by David Wojnarowicz. Made of denim, with a pink triangle on the back, it’s emblazoned with a furious declaration: IF I DIE OF AIDS – FORGET BURIAL – JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.

One thing leads to the other, like a feedback loop; a book becoming (un)bound. My association is one that I’ve made with ghosts, in the hope that they might see, hear, read, a fragment of what’s come after them. Shurin writes about these ghosts, what he calls AIDS apparitions. I’m grateful that Unbound is more than an apparition; that it exists, corporeal, for me to hold in my hand. For me to thumb through while I write this essay.

Aaron Shurin is 75 years old, and an emeritus professor at the University of San Francisco. I wonder how many times he’s walked past the AIDS Memorial at Golden Gate Park, and if he’s ever laid his hand upon the stone, reaching out to those AIDS apparitions. I wonder if he was there, that cold day in November when I went the length and breadth of the city, fitting as many things as possible into a long day that I wished could have stretched on beyond how we think of time. I like to think that he was.

Sam Moore is a writer and editor. They are the author of All my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press), Long live the new flesh (Polari Press), and the forthcoming Search History (Queer Street Press). They are one of the cocurators of TISSUE, a trans reading series based in London.