by David Grundy

Ably edited by scholars Aldon Nielsen—Thomas’ friend and literary executor—and Laura Vrana, The Collected Poems of Lorenzo Thomas is a much-needed volume. It collects all of Thomas’ in- and out-of-print collections—Chances are Few (1979), The Bathers (1981), Sound Science (1978), and Dancing on Main Street (2004)—along with his contribution to the anthology Jambalaya (1975), and a substantial section of previously uncollected work originally published in little magazines ranging from El Corno Emplumado to Umbra, Liberator to C: A Journal of Poetry, Callaloo to Zzzzz1. The book takes its place in a mini publishing boom of work by poets of the African-American innovative tradition hitherto trailblazed in Nielsen’s own scholarly and editing work. Recent examples include new editions of the work of Russell Atkins (Cleveland) and Bob Kaufman (San Francisco), as well as in recent and forthcoming critical work by Lauri Scheyer (Ramey), James Smethurst, Jean-Philippe Marcoux and Harmony Holiday. As these editions and this criticism reveal, such poetry forms a major part of American—and world—poetry that has too often gone ignored by an establishment that remains fundamentally governed by the linked principles of aesthetic conservatism and white supremacy. Thomas, the consummate poet-scholar, was himself a pioneer in redressing such omissions. As a critic, he wrote beautifully about others’ work, and he might well have been the writer best posed to explicate his own history, correcting misconceptions and lazy critical generalisations with a sharp and witty eye for telling detail. In the following, I’ll nonetheless try to catch some sense of Thomas’ life and work in the hopes that it will illuminate a reading of these Collected Poems.

Born in Panama, Thomas moved to New York at the age of five where he to learn English from scratch, and a sense of both productive hybridity and double displacement haunts this work. ‘Black’ but not ‘African American’, as Tyrone Williams has noted, Thomas combined an exile’s sense of trauma with a diasporic, internationalist potentiality2. Thomas was extremely precocious, editing a magazine called Lost World at the age of just seventeen and reading voraciously. At a workshop held by Belgian-Jewish trade unionist and poet Henri Percikow, mainly attended by garment workers, Thomas met another young poet, David Henderson: they both would soon become central members of the Umbra Poets’ Workshop which emerged on New York’s Lower East Side in 1962. Umbra emerged from a confluence of internationalist activism and experimental writing practice. The Umbra poets wrote in a huge variety of styles and registers, providing a receptive environment for Thomas’ own complex voicings, which avoided the pitfalls of dialect stereotypes, ‘protest poetry’, or ornate, Eurocentric imitation. Outside of the nurturing milieu of the workshop, Thomas, like many other Umbra writers, had to struggle with the misinterpellations invariable placed on writers of colour by white critical gatekeepers, who equated nuanced exploration of politics with ‘anger’.3 Irony is key to this early work: neither the irony of despair, of giving up on struggle, nor the knowing irony that serves as decoy for the politics of hatred, but a mode of critical distance that works alongside solidarity, insurgency and the joy of creation. The poems tend toward a wickedly complex syntax, spanning the limits of sentence grammar, as telling line-breaks and enjambments, emphasized by Thomas’ characteristic use of capitalisation at the start of every line, disrupt and extends ostensible sense to telling effect. ‘The Black Canaries Weep Over Gomorrha’—probably Thomas’ very first published poem, from his own Lost World journal—provides one of the most visually striking instances of such work.

[…] strange spaces

b

r

e

a

k

s

our

lips

& split

my w o r d s

(437-8)

Umbra had dissolved by the mid-1960s, but Thomas continued to be involved in New York’s thriving artistic scene, publishing a scarce journal with Ron Padgett, and participating in the birth of the Black Arts Movement. In 1967, he graduated from Queens College and studied for an M.L.S. at the Pratt Institute, publishing his first pamphlet, A Visible Island, with Adlib Press. The following year, he was drafted and, having considered fleeing to Canada, ultimately served in Vietnam. Thomas keenly felt his status as first-generation immigrant and decided to join the navy in the ultimately vain hope of staying out of combat. For a time, he was unable to write, but gradually, he found a way to process the Vietnam experience in his work: most notably, in Fit Music: California Songs, written in 1970, and a section of his second collection The Bathers entitled ‘Slum Days After the War’. Thomas’ Vietnam and post-Vietnam poems are as crucial as the much more famous depictions of the conflict in the work of white poets like Robert Duncan, Denise Levertov and Allen Ginsberg. Unlike them, Thomas actually served in the conflict, a contradiction he renders with keen intensity and with his characteristic irony, likening returning to America as returning to “de Plantation” and asking himself “How did you like being the envoy of a monstrous epic / Or saga of Western corruption” (71).

Adrift in New York after the conflict, at a time when Black Arts and Black Power activists were getting some measure of employment – albeit often precarious – within the academy, Thomas moved South as writer-in-residence at Texas Southern University, Houston, in 1973. Taking up several similar positions in the intervening period, he was appointed to a teaching position at the University of Houston-Downtown in 1984, where he was Professor of English for over two decades. As a poet in residence at public schools, as well as community centres such as Houston’s Black Arts Centre, Thomas conceived of education as part of a broader cultural project, rather than a sequestering into elite institutions. Alongside his professorship, he also helped to organize the Juneteenth Blues Festival in Houston and to edit the magazine Roots, as well as acting as a regular book reviewer for the Houston Chronicle. And it was in Texas that Thomas’ career as a scholar began in earnest, in a series of essays published in the wave of new Black literary journals that emerged thanks to the gains of Black Arts activism such as Obsidian and Callaloo. As a critic, Thomas maintained the same wry, deft touch as his poems: often deceptively straightforward, he’d underscore a particular historical irony with a telling turn of phrase, or make the case for neglected poets with a passionate intensity that, one felt, could do justice to anyone.4 The objects of his attention were not always expected – perhaps my favourite of all his turns-of-phrase comes in an essay on Frank Stanford, whom he unforgettably describes as a “swamprat Rimbaud”.5 This range of reading also fed his poetry. In a statement for Michael Lally’s 1976 anthology None of the Above, reprinted as an appendix to the present volume, Thomas lists as influences the neglected Marxist theorist Christopher Caudwell, golden child of the Auden generation who was tragically killed whilst fighting in the Spanish Civil War; Hazrat Inyat Khan, founder of the international Sufi movement; Victorian Egyptologist Gerald Massey; and Vietnamese turn-of-the-century poet Tran Te Xuong (whose work Thomas translated). “I can understand it if you haven’t heard of some of these people”, Thomas concludes. “But you will”. (497)

As the decade turned, Thomas’ relative career security enabled him to publish two full-length poetry books in quick succession. Chances are Few (1979) and The Bathers (1981), the latter published by his friend and Umbra colleague Ishmael Reed, collected work from both the 1960s and 1970s, and are dazzling examples of Thomas’ sheer range. In general, Chances are Few concentrates on poems which address the pleasures, pains and ironies of personal relationships (what one poem calls “personal anthropology”). ‘MMDCCXIII ½’, a sonnet which meditates on the legacies of “slumlord greed and desperate privacies” that haunt those arrangements we call ‘domestic’, is concision in itself: the volume also contains lengthy, brilliant meditations on race, music and cinema ‘Screen Test’, ‘Class Action’, ‘Big House Movies’ and ‘Hat Red’, along with translations or poems ‘after’ Leon Damas, Dukardo Hinestrosa, Ovidio Martins and Tran Te Xuong. The Bathers is oriented towards more explicitly ‘political work’, from the ‘Early Crimes’ previously published in Black Arts venues like Liberator and Black Fire to Fit Music, Dracula and the long title poem, a retrospective meditation on the 1963 Birmingham Civil Rights campaign which stands as one of his most important pieces. The book also collects Thomas’ 1975 chapbook Framing the Sunrise – a brilliant meditation on television, the “masked media” and the mendacity of American politics in the era of Attica and Vietnam – and poems on the murder or Pablo Neruda, the aforementioned section of post-Vietnam work, and a section which Thomas calls with characteristically deceptive simplicity ‘Euphemysticism’.

Thomas’ pun suggests scepticism to the way that euphemism—the concealing of a blunt and unpleasant reality—is elevated to a kind of spiritual status. Top of the list of such ‘euphemystic’ double-speak lies the explaining away of persistent racism, if not as a necessary evil, then certainly an unavoidable one. Gradualism, apologias, the wilful turning of blind eyes: what are such refusals to face up to a difficult reality but mystical beliefs in an un-alterable reality? Given this, Thomas performs a swift and smart reversal, revealing the pseudo-rationalist ‘common sense’ of whiteness to be neither common nor sensical, and the derided, non-European mysticism of peoples of African descent to contain within it a good deal of common sense. Particularly in his poetry of the 1970s, Thomas operates under the influence of Sun Ra, whom he knew in the 1960s, as well as his own esoteric studies in the work of Gerald Massey and “the Egyptian syllabary”. Such work anticipates the rich esoteric tradition of poets such as Will Alexander, Nathaniel Mackey and Jay Wright. ‘Jubilee’ is a free translation of a hieroglyphic inscription, and in ‘The Bathers’, the “shameful English” in which “ancient words” are spoken is suddenly interrupted by the appearance of a hand-drawn set of hieroglyphs which lift above the fire-hoses, bombs and police dogs wielded by the racists of Birmingham, Alabama. Here, the hieroglyph seems to exist somewhere between sound and symbol, an image and aural force that provides the basis for calls ‘Sound Science’: a force-field, a presence that, for Thomas, also a quite material collective resource. In such work, the spiritual is a tool of both literal and metaphoric survival, inhering in Afro-Futuristic transmutations and transmission which resist the violent severing of ancestral links.

In ‘Spirits You All’, a poem for saxophonist Charles Gayle, Thomas will memorably term this “Church if you feel it”. Experienced through music, in a fusion of free jazz and mambo rhythms, church here is a verb as much as a noun, a container for a felt collectivity and a felt history. And music—an inherently immaterial form, yet of great material import—is central to this aesthetic. Like many of his peers, Thomas was a keen attendee of New York’s jazz clubs, teeming as they were with an almost unimaginable profusion of invention and discovery. Thomas’ use of music goes beyond merely registering performer, ambiance or milieu, however: instead, music becomes a kind of cultural weapon, from the anti-colonial threat posed by Charles Mingus in ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ to a Sonny Rollins like none you’ve heard before in ‘Modern Plumbing Illustrated’, in which Rollins appears to assault popular white evangelist Oral Roberts. Elsewhere, Thomas’ attuned ear goes all the way from ‘progressive reggae’ to R&B and country music, picking up the ditties on the radio station, from radio DJ Jocko to the Shirelles to the sentimental afternoons of Marlene Shaw (whose ‘Lazy Afternoon’ is shaded by the transformation on The World of Cecil Taylor), radio serving as both conduit for cosmic exploration (as per some of Jocko’s theatrics on the Rocket Ship Show) and a form of “wallpaper”, “composed by amateurs and marketed by pros” (282). Thomas is keenly conscious of the material circumstances bind and separate listeners and musicians alike. In ‘Historiography’, a poem written to be performed with a jazz combo, the speaker undercuts the tragic romanticism read into the life and death of Charlie Parker by insisting that, whatever cosmic hieroglyphs Parker’s music conjured, “Bird was a junkie” (88). Nonetheless, in Thomas’ understanding, art, particularly music, hold out a promise in the midst of death-dealing technocratic rationalism, commercial imperatives, exploitation and appropriation. As Thomas writes, this poetry is “an effort to welcome a better world. I see things & write them down & call it poetry, though they used to teach us this was ‘fantasy’. It’s not”. (496) Fantasy, the spiritual, the imagination—all those forces which white supremacy derides and delimits, often through racialised caricatures and affective stereotyping—are the weapons and anti-weapons that poetry has at its disposal, for “poetry is an instrument that we study in order to free the spirit”.

Thomas’ next, and final, full-length collection, Dancing on Main Street, had to wait until the new millennium to see publication. The book ranges from very early work to poems in his characteristic late style, in which a new simplicity of expression – which is, as ever, deceptively complex in its political thinking – evinces a vital compassion. In the extraordinary ‘Dirge for Amadou Diallo’, Diallo’s death as an undocumented migrant serves as the inverse of Thomas’ own life, which could be interpellated into the narrative of the ‘success story’. “It is hard to have your son die / In a distant land / And harder still / When we can’t understand” (407). Thomas’ 9/11 poem ‘Ailerons and Elevators’, with which it originally appeared in the 2004 chapbook Time Step, sets Richard and Orville Wright’s famed flight alongside their classmate Paul Laurence Dunbar’s own ‘ascent’ as an elevator boy in downtown Dayton (“Their neighbours knew / That they’d go up high in this world”, Thomas drily remarks), the planes used to firebomb black residents of Tulsa in 1921 such as newspaper editor Andrew Smitherman, who organised African-American resistance against mob violence and was – with the perversity characteristic of white supremacy – blamed for inciting the massacre, and the ghost of the World Trade Centre attacks of the previous year. The political analyses in such poems are made with a sardonic yet compassionate quietness that sacrifices not one iota of justified anger. Though quiet, these poems are passionately oriented against injustice rather than lingering in pessimism, melancholy or despair. They insist on countering the “bread and circuses” of wars on terror, anti-Black violence, and the assault of consumer culture with a linguistic clarity that is a necessary and saving grace, refusing to let their readers forget the histories of injustice left out of the official record. This is, as one the section titles in Dancing on Main Street has it, “resistance as memory”. In ‘Airelons’, “From two backyards away / The Funkadelics and Jay-Z resist denial” (491). In a real sense, The Funkadelics and Jay-Z—and Thomas himself—provide sustenance, material for living. To resist denial, to condemn that which would deny resistance, to hear in several registers at once the affirmation of survival in the face of death.

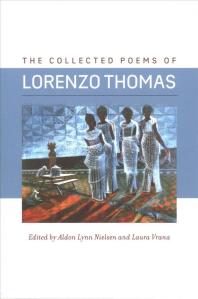

The present volume ends with a tribute to the late, Houston-based artist John T. Biggers, whose work graces the cover. Typically modest in its ambition, ‘An Arc Still Opens’ turns a tribute to Biggers into a thesis on the origin and role of art.

The ancients said,

Losing an elder

Is to lose a library

Then they invented Art

To stem such loss

(492)

In “world of entropy and haste”, a “vast depot”, to focus on the past is also to look towards the future. History is lived and still living. Thomas’ poem reminds us of that, of time’s tricks and of poet’s orphic capacity to cast beyond the material constraints that cut us apart in the morass of global politics—that is, the basic facts of our daily, interconnected lives. If you care about poetry, you should read this book.

But, as Thomas put it:

You don’t have to take my word

For “it”

(290)

1 Thomas was a prolific little magazine contributor: since the book went to press, a selection of further poems have come to light, which might hopefully see the light of day in the not-too-distant future.

2 Tyrone Williams, ‘My Lorenzo Thomas: His Stand-Alone Blues’. Delivered as a paper at the African American Literature and Culture Society Symposium, St. Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri, October 25-27 2007.

3 A recently-digitised conversation between Thomas and Michael Silverton on WNYC is a case in point. The conversation can be heard at: https://www.wnyc.org/story/reel-11-lorenzo-thomas/.

4 The fruits of these scholarly endeavours wouldn’t fully manifest themselves until the Millennium turned. Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2000) was the summation of Thomas’ critical work. An argument in part about canonicity, and the erasure of African-American poets from histories of American modernism in which they were central, Thomas’ range was broad – from the competition between William Stanley Brathwaite’s The Poetry Journal and Anthology of Magazine Verse and Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine, and the work of Chicago-based Fenton Johnson and of the great Margaret Walker, through to the Black Arts movement, in which Thomas’ personal experience of the era adds both depth and lightness to the stories he tells (the chapter on Baraka has a killer anecdote about visiting Baraka at the height of the Newark rebellion), ‘Louisiana voices’ such as Ahmos Zu-Bolton, and a concluding chapter on younger poets such as Harryette Mullen, whom Thomas mentored and who returned the favour with a pair of beautiful essays on his work. A book on Black music from blues to hip-hop, edited by Aldon Nielsen, appeared posthumously as Don’t Deny My Name: Words and Music and the Black Intellectual Tradition in 2008.

5 Lorenzo Thomas, ‘Finders, Losers: Frank Stanford’s Song of the South,’ Sun & Moon: A Journal of Literature and Art, no. 8 (Fall 1979): 8-23.

David Grundy is a poet and scholar based in London. He is the author of A Black Arts Poetry Machine: Amiri Baraka and the Umbra Poets (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019) and Present Continuous (Pamenar Press, 2022), and co-editor, with Lauri Scheyer, of Selected Poems of Calvin C. Hernton (Wesleyan University Press, 2023). He co-runs the small press Materials/Materialien.