IN MEMORY OF JOSHUA CLOVER, COLE HEINOWITZ, ALICE NOTLEY & FANNY HOWE

FEATURING: Sara M Saleh, Joni Prince, Shatr Collective, Carlos Soto Román, Petra Kuppers, Diane Ward, Dianna Settles, Mayra Santos-Febres translated by Seth Michelson, Elena Gomez & Chelsea Hart, Noah Mazer, Daniel Borzutzky, Ash(ley) Michelle C., Ghazal Mosadeq, Darius Simpson, Mohammed Zenia, Mario Payeras translated by Dan Eltringham, Ferreira Gullar translated by Chris Daniels, Christophe Tarkos translated & read by Marty Hiatt

REVIEWS: Andrew Spragg on Tom Raworth, Matthew Rana on Ida Börjel, & Paisley Conrad on Harryette Mullen

230 pages. $16.

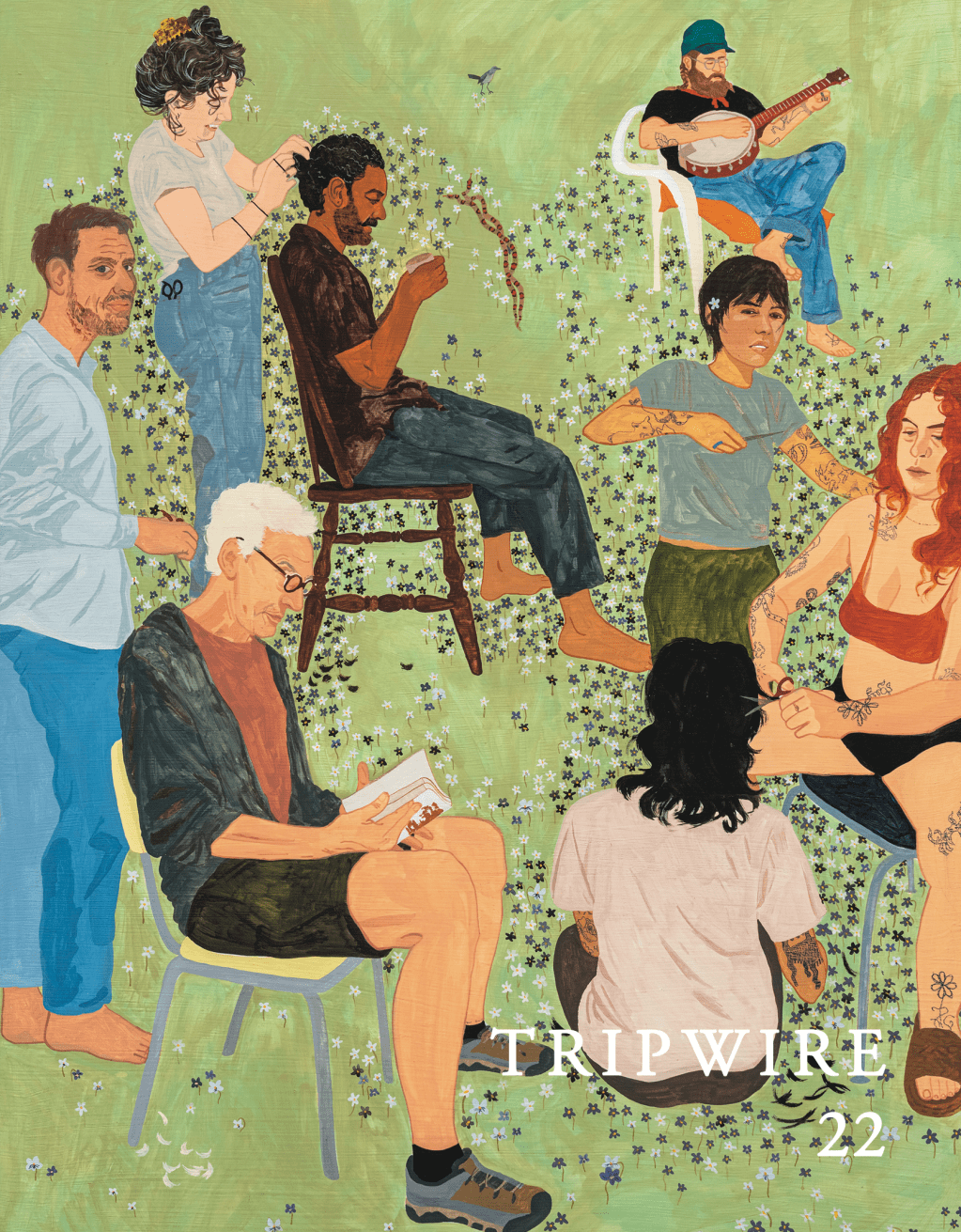

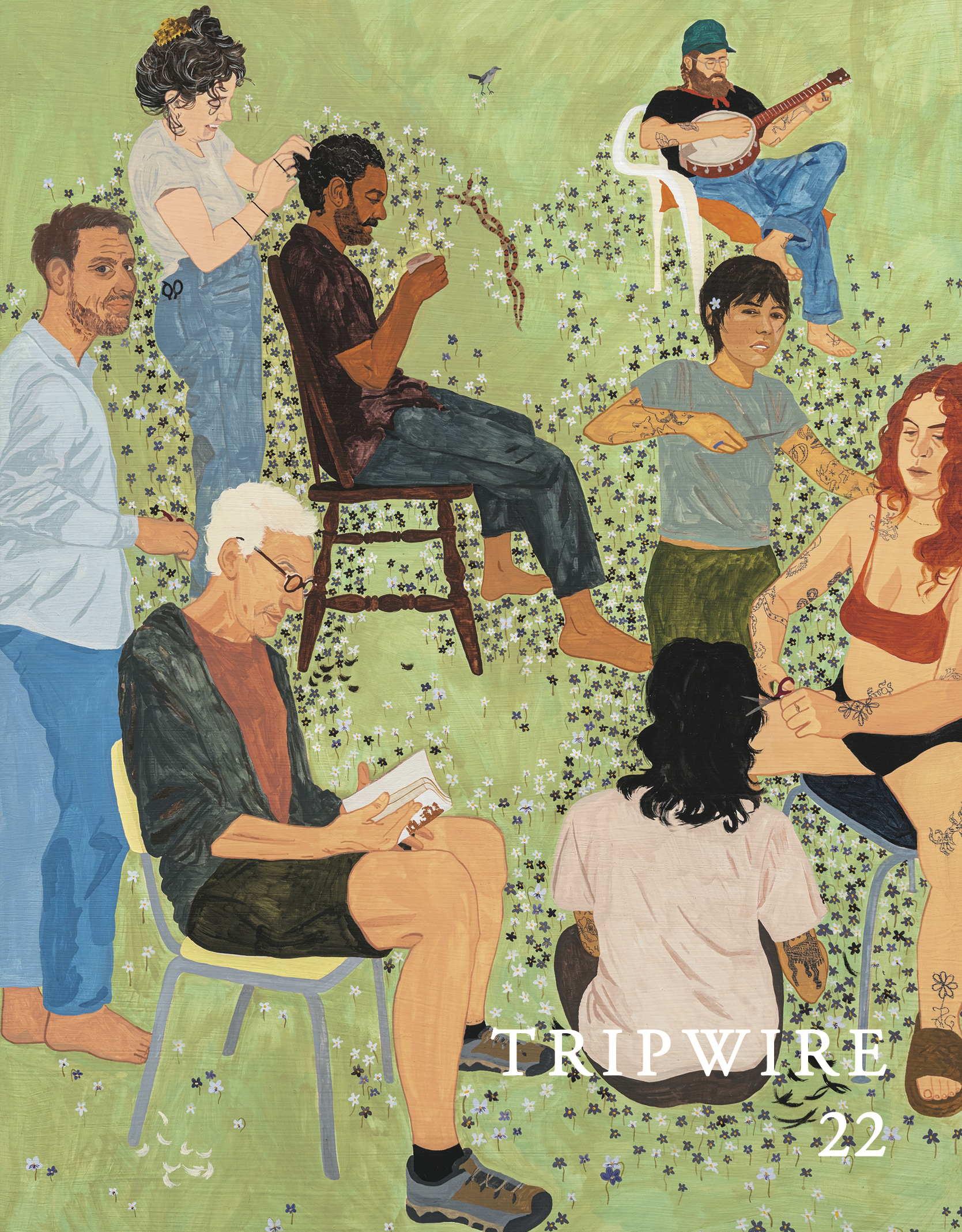

TRIPWIRE 22, $16

US (+ $4 shipping)

International (via Asterism)

Digital PDF $5